About the Author: Lee Anna Maynard, PhD, is a freelance writer, editor and scholar currently based out of Augusta, GA, where she is on faculty with Augusta University. She received her PhD in English from the University of South Carolina and was an Assistant Professor in the Department of English and Philosophy for Auburn University Montgomery. She has served as the managing editor for a regional magazine and her first academic volume, which explores the role of boredom in the Victorian novel, was published in 2009.

Perry Roquemore Becomes Director

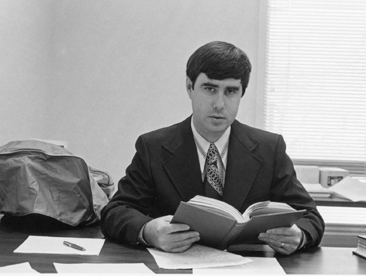

From the moment he sat in front of a quietly humming electric typewriter in the nearly-new Adams Avenue building to record his thoughts on the 1975 legislative session for the still-running Legislative Bulletin, Perry Roquemore was plugged-in to the needs of the League’s member municipalities. A Montgomery native who returned home after his higher education in Tuscaloosa to accept the Staff Attorney position offered by John Watkins and the Alabama League of Municipalities, Roquemore became not only an expert with an encyclopedic knowledge of municipal law but an effective and loyal advocate of towns’ and cities’ interests. Like his mentor at the League, Roquemore found that preparedness, professionalism, and a genuine stake in the fortunes and fates of the League’s cities and towns made his a voice that was heard and heeded by the Alabama Legislature.

When Roquemore assumed command in the mid 1980s, he faced a state and nation considerably different from what Ed Reid or John Watkins had encountered. The Berlin Wall, that symbol of communist separation and power constructed during Watkins’ early years as Executive Director, was toppled during this decade, and the space race so hotly contested between America and the Soviet Union in the 1960s was largely over, though the dangers of space flight had not yet been mastered, as the 1986 explosion of the space shuttle Challenger tragically demonstrated. Strides toward more demographically representative officeholders in Alabama politics were made in this decade and reflected in the leadership of the League, which saw its first woman president – Nina Miglionico (Birmingham’s City Council President) for 1981-1982 – and its first African-American president – Johnny Ford (mayor of Tuskegee) for 1989-1990. Minorities of race and gender still encountered plenty of obstacles in the workplace, as the films 9 to 5 and Trading Places made painfully – if laughingly – clear, and power and greed were not only accepted but sometimes embraced in business environments, as three of the decade’s bestselling books confirmed: Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, Donald Trump’s Surviving at the Top, and Lee Iacocca’s self-titled autobiography. “Greed is good” asserted Gordon Gekko, the take-no-prisoners stock trader in Wall Street, and the popularity of television programs like Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, Falcon Crest, and Dynasty revealed the fixation middle-class America developed for millionaire culture.

The television itself, a staple in the American home since the late 1950s and early 1960s, took a larger and larger role in the daily life of the average American during the 1980s. MTV debuted and captivated a generation of teenagers with music videos that became increasingly sophisticated and well-produced as the decade advanced (and that changed the rules about what qualifications were necessary to become a successful pop artist). With the advent of Betamax and VHS technology, videotapes became an easy and cost-effective entertainment and information option. Whether you wanted to join the exercise craze and practice aerobics with Jane Fonda and Richard Simmons or learn every line from your favorite movie, the videotape player made it possible. New Executive Director Roquemore was in touch with the preoccupations and the defining medium of our age: he availed himself of the new video technology to begin amassing an impressive home collection of complete episodes of television series, creating a research-grade archive over the next twenty-five years.

Home gaming systems like Atari that hooked up to televisions made preserving “Pac-Man” and fighting “Space Invaders” top priorities for students and adults alike in the 1980s. In a military move that seemed eerily akin to the new video-gaming options, President Ronald Reagan announced the development of the Strategic Defense Initiative (or, as critics renamed it, “Star Wars”), which was meant to be capable of shooting down incoming nuclear missiles (presumably Soviet) in space before they entered the United States’ atmosphere. With the Cold War threat soon receding under the glasnost policies of Gorbachev, however, America’s focus shifted to dangers from within. First Lady Nancy Reagan’s plea to kids to “Just say no!” to illegal drug use was timely: smokeable crack cocaine, with its cheaper and easier production and quick-acting, intensified high, swept the nation, and drug-users’ sharing needles contributed to the growing AIDS epidemic.

Expanding Insurance Services

Alabama’s cities and towns also faced dangers from within in the 1980s, including unreasonable (and unfunded) legislative demands and the dilemma of providing insurance coverage for their municipal employees. Unfunded state and federal mandates, approved by Congress and the Legislature, were requiring ever more from municipalities without providing any revenue to pay for the added requirements, duties, or services. In 1988, the League of Municipalities successfully promoted a constitutional amendment that restricted the Alabama Legislature’s authority to force unfunded mandates onto towns and cities. Municipal governments, their hands already full from coping with the increasing number of federal and state mandates that altered their operations, had the further complication in the 1980s of discovering that health insurance coverage for their workers was quickly becoming either too expensive or completely unavailable. In answer to the distress of its constituent municipalities, the League lobbied the state Legislature to allow the State Employees Insurance Board to establish a health insurance plan for municipal employees. As a result, many towns and cities were able to obtain and afford health coverage and retain valued employees.

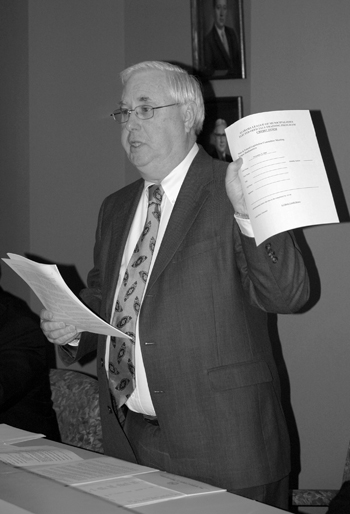

The insurance crisis Alabama’s municipalities faced extended beyond securing health coverage for municipal employees – liability insurance also proved elusive. To resolve the problem, Roquemore, along with former mayor of Pine Hill and past League President Harold Swearingen and several other municipal officials, founded the Alabama Municipal Insurance Corporation (AMIC). To this day, AMIC provides competitively-priced coverage to many of the League’s member municipalities. The revenue generated by AMIC (as well as MWCF) has funded the extension and expansion of the League of Municipalities’ member services.

Saving Money and Time

Though conspicuous consumption characterized many Americans’ lifestyles in the 1980s and early ’90s, Alabama’s municipalities and the League that represented their interests shared a diametrically opposed agenda: rather than “spend, spend, spend,” their motto could well have been “save, save, save.” To help municipalities find reliable sources of funding and also curtail spending where possible, the League successfully pursued legislation that allowed cities and towns to charge sales tax on vehicles bought and sold among private parties; that instituted a revolving loan fund to aid in financing wastewater-treatment programs; that capped the financial liability of municipal officials and employees when engaged in their municipal duties; and that allowed towns and cities to save money by changing methods of rezoning notifications.

Reinvesting revenues from the AMIC and MWCF programs into the League generated an even higher and more efficient level of member assistance. Upon Roquemore’s advice, the League’s Board of Directors voted in the early 1990s to triple the size of the headquarters, from 7500 square feet to 22,000. The building expansion was completed in 1992, and its additional office space has since allowed for hiring more employees and accommodating updated technology that facilitates easy and speedy communication with the Capitol and member municipalities, including fax machines, numerous incoming phone lines, high-speed copiers, in-house video and audio production facilities, a highly-trafficked Web site, and state-of-the-art computer systems. Instead of activating phone trees or relying solely on the U.S. Mail (or, in emergency situations, Greyhound buses) to relay important documents or notify constituents of critical votes or events, the League’s skilled staff can share the information almost instantaneously.

Another way Roquemore aimed to save his member municipalities time and money was by aiding in the creation of more effectual municipal leaders. Under his leadership, the League expanded and extended its voluntary training programs, offering not only annual windows for professional growth at the League convention but frequent long- and short-term educational opportunities with curricula virtually guaranteed to improve efficiency. By the mid 1990s, the League’s member municipalities numbered 421, and the officials representing these towns and cities (averaging six per municipality) were often better educated but less experienced in governance than their predecessors. The League’s Certified Municipal Official training program (CMO) took off in 1994, and the response was so great that the League later implemented Advanced Certified Municipal Official training. Learning about the expectations, restrictions, and possibilities of municipal office has now equipped more than 3300 local government leaders to make more effective use of their time in office. The League’s extremely successful CMO program, the second such in the United States, has cultivated future League leaders as well as better-educated local municipal leaders. In addition, it has served as a model program for sister organizations throughout the country.

In the late 1990s, the groundwork laid by the League in the early ’80s to secure municipalities’ fair share of oil trust-fund revenues was jeopardized when the Legislature realized that, for the first time, the interest on the funds was going to exceed $60 million and they would have to deliver on their promise to Alabama’s towns and cities. The League mounted a quick defense of the municipalities’ share, pursuing it so far as to win a constitutional amendment to preserve the municipal portion. This rapid response to the threat ensured what has now been a decade of additional revenues for municipalities’ capital improvements.

Throughout its history, the League has also worked closely with the National League of Cities (NLC) in Washington, D.C. (as well as its predecessor, the American Municipal Association) to protect the interests of municipalities at the national level. Alabama has consistently brought one of the highest numbers of delegates to NLC’s national meetings, including the annual Congress of Cities and the Congressional City Conference (held each year in D.C.) and has had League members serve on the national board, including the first Alabama official to be elected to the coveted position of NLC president – Councilwoman Cynthia McCollum of Madison (2007-2008).

Protecting and Nurturing Municipalities

With the new millennium came new challenges for Alabama’s municipal officials. After a day and night transfixed in front of their televisions and glued to their telephones, Americans reemerged from their homes on September 12, 2001 to a world transformed, a place they now perceived as vulnerable, targeted, and fundamentally less self-assured. As the nation scrambled to cope with the immense loss of life, property, and confidence in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks, municipal officials were expected to generate plans to produce more secure communities and to cooperate with all state and federal requests to supplement homeland security. The League of Municipalities leapt into action, creating many seminars to help local officials understand and promote mechanisms to defend and secure their cities and towns as well as the state and nation.

Just as the League helped municipalities adjust to the new realities of city and town administration in post-9/11 America, it had facilitated municipalities’ banding together to come to one another’s aid in times of calamity. Alabama’s susceptibility to flooding, tornados, hurricanes, and other natural disasters means that towns and cities of all sizes might be suddenly facing momentous clean-up or recovery efforts, and the League of Municipalities successfully lobbied for legislation that authorized municipalities to provide assistance – in the form of a gift or loan – to any other municipality or county in the state, so long as a state of emergency was declared by the Governor or the President. This cooperative spirit is symbolic of the modern League’s philosophy – the feeling that spurred the banding together of towns and cities to take a stand against an unresponsive but all-powerful state legislature back in 1935. The power of pooling resources and standing together infuses one of the League’s most recent undertakings, the Alabama Municipal Funding Corporation. Founded only a few years ago, this program empowers member municipalities to obtain funding that would otherwise be beyond their grasp, funding that can be used for virtually any municipal project.

As the League’s services and responsibilities have grown, so has its staff. In the last twenty-five years, the association’s workforce has more than tripled in size to over 60 skilled professionals. The number of member municipalities has grown from the initial 24 to 444, an impressive 99 percent of the municipal population of the state, and, accordingly, the demand for information and assistance has increased. In 2009, League attorneys fielded more than 12,000 inquiries from Alabama’s town and city officials.

The League in 2010 boasts a custom-designed and generously-sized headquarters. Its initial and ongoing concern with gathering and spreading information is now aided by VOIP phone systems, blast e-mail alerts, and slick, professional publications. Ed Reid, John Watkins, and their staff attorneys were veritable one-person lobbying forces, but for today’s more complex political landscape, the League employs dedicated personnel to advance the member municipalities’ interests. Reid and Watkins worked to remove legislative stumbling blocks and to respond to and defend against intrusive power structures, while Perry Roquemore and his team have been able to focus their efforts on pursuing proactive legislative measures and expanding educational, financial, and quality-of-life opportunities for their members. Back in Depression-era Alabama, Ed Reid and the founding members of the modern incarnation of the League could little have imagined how successful their vision of an empowered and autonomous body of municipal officials would become.

Amidst all the change, the unifying principles of the League remain constant: as 97-year-old former Fayette Mayor and past League President Guthrie Smith succinctly put it: “There’s more to city government than filling pot holes and catching stray cats.”